The "Eretria of America"

Having grown somewhat tired of the continued presence of their Persian appointed tyrants1 on the sacred soil of Asia Minor- not to mention the annoying Persian habit of constantly sending locals to drab committee meetings in their stead, repeatedly demanding that underlings retrieve fresh coffee, and generally not recognizing their contributions to the Empire at large- Cyprus, Caria, Aeolis, and Doris banished or executed their Persian appointed tyrants and declared themselves free of Persia. The resulting nastiness, which was in no small part encouraged by the tyrant Aristagoras attempting to save his own skin by inciting his charges, the Milesians, into revolt first, is generally termed the "Ionian Revolt."

As a conflict, the Ionian Revolt is as rich and complex as they come, involving as it does a host of allies, some with competing interests, complex, overlapping promises, assurances, supporting roles in campaigns, amphibious landings and retreats, and (what conflict would be complete without?) the ancient contest between Persian cavalry, and the phalanx.

Given the propensity of Ionian shenanigans to spark broader conflicts it is little wonder that the 3rd Viscount Palmerston (Knight of the Most Noble Order of the Garter, Knight Grand Cross of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath, Member of the Most Honourable Privy Council) regarded as so delicate the matter of the Ionian islands during the "Don Pacifico Affair" that he barely mentioned them at all during the oration that would later become known as the "Civis Romanus sum" speech.

But, alas, dear reader, a comprehensive exploration of the Ionian Revolt (or the 3rd Viscount Palmerston) would be a laborious undertaking mandating, as it surely would, exploration of the voluminous Volumes chronicling the Greco-Persian wars, for which the revolt serves as a sturdy, left-most bookend. Still, a particular aspect of this later conflict bears some mention as finem respice explores the subject that arouses the instant text. Specifically, finem respice turns the aperture of her expository prose to one particular incident of note: The Battle of Marathon.

Some of finem respice's more venerable readers may remember a time (like during the Nixon administration) where any higher-education-bound young man or woman hailing from the developed (and many from the developing) world might explain the origins of the word "Marathon" by describing how the distance runner Pheidippides ran from Marathon to Athens to announce the result of the battle, which he did in a single word just before expiring on the spot.

Art historians (by which finem respice means those who derive their understanding of history solely from art) will recognize the truth of this legend in pieces like Luc-Olivier Merson's "Le Soldat de Marathon," for which the artist won the Prix de Rome in 1869:

And There Was Much Rejoicing! 2

The subject also moved no less an artist than Jean-Pierre Cortot (whose work "Le Triomphe de 1810" graces the Arc de Triomphe in Paris) to sculpt "Le Soldat de Marathon Annonçant La Victoire":

Obliquely and Beautifully Suggesting the Divinity of the Athenians? 3

Of course this tale is apocryphal.

In the amorphous and miasmic world of ancient history apocryphal stories are par for the course and the long grinding war of attrition for which truth is the ultimate casualty continually erodes facts and evidence until one is left only with tattered and rotted parchments posing as authoritative sources.

Fortunately, in this case we have the inestimable fortune to have the works of Herodotus to lean on. So important are the methods and resulting works of Herodotus considered that he is regularly referred to as the "Father of History" (though his many critics would be quick to modify that honorific to read "The Father of Lies").

Unlike many chroniclers of the time, Herodotus is thought to have travelled widely in compiling the research that he eventually transformed into his works. Indeed, his penchant for skepticism was almost unique among his contemporaries (and would remain so for centuries afterwards). This, along with his temporal proximity to the events, suggests that while they might not be ideal, there is much to commend Herodotus' works to our gentle review. He begins:

These are the researches of Herodotus of Halicarnassus, which he publishes, in the hope of thereby preserving from decay the remembrance of what men have done, and of preventing the great and wonderful actions of the Greeks and the Barbarians from losing their due meed of glory; and withal to put on record what were their grounds of feuds.4

Of this it is somewhat difficult to scoff. Fully five books later we arrive at the Battle of Marathon:

The barbarians, after loosing from Delos, proceeded to touch at the other islands, and took troops from each, and likewise carried off a number of the children as hostages. Going thus from one to another, they came at last to Carystus; but here the hostages were refused by the Carystians, who said they would neither give any, nor consent to bear arms against the cities of their neighbours, meaning Athens and Eretria. Hereupon the Persians laid siege to Carystus, and wasted the country round, until at length the inhabitants were brought over and agreed to do what was required of them.

Meanwhile the Eretrians, understanding that the Persian armament was coming against them, besought the Athenians for assistance. Nor did the Athenians refuse their aid, but assigned to them as auxiliaries the four thousand landholders to whom they had allotted the estates of the Chalcidean Hippobatae. At Eretria, however, things were in no healthy state; for though they had called in the aid of the Athenians, yet they were not agreed among themselves how they should act; some of them were minded to leave the city and to take refuge in the heights of Euboea, while others, who looked to receiving a reward from the Persians, were making ready to betray their country. So when these things came to the ears of Aeschines, the son of Nothon, one of the first men in Eretria, he made known the whole state of affairs to the Athenians who were already arrived, and besought them to return home to their own land, and not perish with his countrymen. And the Athenians hearkened to his counsel, and, crossing over to Oropus, in this way escaped the danger.

The Persian fleet now drew near and anchored at Tamynae, Choereae, and Aegilia, three places in the territory of Eretria. Once masters of these posts, they proceeded forthwith to disembark their horses, and made ready to attack the enemy. But the Eretrians were not minded to sally forth and offer battle; their only care, after it had been resolved not to quit the city, was, if possible, to defend their walls. And now the fortress was assaulted in good earnest, and for six days there fell on both sides vast numbers, but on the seventh day Euphorbus, the son of Alcimachus, and Philagrus, the son of Cyneas, who were both citizens of good repute, betrayed the place to the Persians. These were no sooner entered within the walls than they plundered and burnt all the temples that there were in the town, in revenge for the burning of their own temples at Sardis; moreover, they did according to the orders of Darius, and carried away captive all the inhabitants.

The Persians, having thus brought Eretria into subjection after waiting a few days, made sail for Attica, greatly straitening the Athenians as they approached, and thinking to deal with them as they had dealt with the people of Eretria. And, because there was no Place in all Attica so convenient for their horse as Marathon, and it lay moreover quite close to Eretria, therefore Hippias, the son of Pisistratus, conducted them thither.

When intelligence of this reached the Athenians, they likewise marched their troops to Marathon, and there stood on the defensive, having at their head ten generals, of whom one was Miltiades.

[...]

It was this Miltiades who now commanded the Athenians, after escaping from the Chersonese, and twice nearly losing his life. First he was chased as far as Imbrus by the Phoenicians, who had a great desire to take him and carry him up to the king; and when he had avoided this danger, and, having reached his own country, thought himself to be altogether in safety, he found his enemies waiting for him, and was cited by them before a court and impeached for his tyranny in the Chersonese. But he came off victorious here likewise, and was thereupon made general of the Athenians by the free choice of the people.

And first, before they left the city, the generals sent off to Sparta a herald, one Pheidippides, who was by birth an Athenian, and by profession and practice a trained runner. This man, according to the account which he gave to the Athenians on his return, when he was near Mount Parthenium, above Tegea, fell in with the god Pan, who called him by his name, and bade him ask the Athenians "wherefore they neglected him so entirely, when he was kindly disposed towards them, and had often helped them in times past, and would do so again in time to come?" The Athenians, entirely believing in the truth of this report, as soon as their affairs were once more in good order, set up a temple to Pan under the Acropolis, and, in return for the message which I have recorded, established in his honour yearly sacrifices and a torch-race.

On the occasion of which we speak when Pheidippides was sent by the Athenian generals, and, according to his own account, saw Pan on his journey, he reached Sparta on the very next day after quitting the city of Athens- Upon his arrival he went before the rulers, and said to them:-

"Men of Lacedaemon, the Athenians beseech you to hasten to their aid, and not allow that state, which is the most ancient in all Greece, to be enslaved by the barbarians. Eretria, look you, is already carried away captive; and Greece weakened by the loss of no mean city."

Thus did Pheidippides deliver the message committed to him. And the Spartans wished to help the Athenians, but were unable to give them any present succour, as they did not like to break their established law. It was then the ninth day of the first decade; and they could not march out of Sparta on the ninth, when the moon had not reached the full. So they waited for the full of the moon.5

As to the continued perversion of Pheidippides' amazing accomplishment (running the nearly 150 miles between Athens and Sparta in two days, and then back) we have no further to look than the prototypical corrupter of truth in favor of propaganda, that purveyor of the thick, acrid syrup of statist glory without regard to its human cost, a notorious and corrupt destroyer of wealth in all its forms, and an entity these pages have dealt with before. Of course, finem respice refers to the International Olympic Committee.

It was probably difficult to find athletes to participate in a two day non-stop run back in 1896 (much less a four day round trip). The 26.2 miles between Marathon and Athens probably seemed at least a bit more appealing, even if that part of the story had little historical basis.

But leaving aside for the moment questions of authenticity or legitimacy (which are universally easy to resolve when the International Olympic Committee is involved) the events leading up to and during the Battle of Marathon are instructive.

The Athenian generals were divided in their opinions; and some advised not to risk a battle, because they were too few to engage such a host as that of the Medes, while others were for fighting at once; and among these last was Miltiades. He therefore, seeing that opinions were thus divided, and that the less worthy counsel appeared likely to prevail, resolved to go to the Polemarch, and have a conference with him. For the man on whom the lot fell to be Polemarch at Athens was entitled to give his vote with the ten generals, since anciently the Athenians allowed him an equal right of voting with them.

"With thee it rests, Callimachus, either to bring Athens to slavery, or, by securing her freedom, to leave behind thee to all future generations a memory beyond even Harmodius and Aristogeiton. For never since the time that the Athenians became a people were they in so great a danger as now. If they bow their necks beneath the yoke of the Medes, the woes which they will have to suffer when given into the power of Hippias are already determined on; if, on the other hand, they fight and overcome, Athens may rise to be the very first city in Greece. How it comes to pass that these things are likely to happen, and how the determining of them in some sort rests with thee, I will now proceed to make clear. We generals are ten in number, and our votes are divided; half of us wish to engage, half to avoid a combat. Now, if we do not fight, I look to see a great disturbance at Athens which will shake men's resolutions, and then I fear they will submit themselves; but if we fight the battle before any unsoundness show itself among our citizens, let the gods but give us fair play, and we are well able to overcome the enemy. On thee therefore we depend in this matter, which lies wholly in thine own power. Thou hast only to add thy vote to my side and thy country will be free, and not free only, but the first state in Greece. Or, if thou preferrest to give thy vote to them who would decline the combat, then the reverse will follow."

Miltiades by these words gained Callimachus; and the addition of the Polemarch's vote caused the decision to be in favour of fighting. Hereupon all those generals who had been desirous of hazarding a battle, when their turn came to command the army, gave up their right to Miltiades. He however, though he accepted their offers, nevertheless waited, and would not fight until his own day of command arrived in due course.

Then at length, when his own turn was come, the Athenian battle was set in array, and this was the order of it. Callimachus the Polemarch led the right wing; for it was at that time a rule with the Athenians to give the right wing to the Polemarch. After this followed the tribes, according as they were numbered, in an unbroken line; while last of all came the Plataeans, forming the left wing. And ever since that day it has been a custom with the Athenians, in the sacrifices and assemblies held each fifth year at Athens, for the Athenian herald to implore the blessing of the gods on the Plataeans conjointly with the Athenians. Now, as they marshalled the host upon the field of Marathon, in order that the Athenian front might he of equal length with the Median, the ranks of the centre were diminished, and it became the weakest part of the line, while the wings were both made strong with a depth of many ranks.

So when the battle was set in array, and the victims showed themselves favourable, instantly the Athenians, so soon as they were let go, charged the barbarians at a run. Now the distance between the two armies was little short of eight furlongs. The Persians, therefore, when they saw the Greeks coming on at speed, made ready to receive them, although it seemed to them that the Athenians were bereft of their senses, and bent upon their own destruction; for they saw a mere handful of men coming on at a run without either horsemen or archers. Such was the opinion of the barbarians; but the Athenians in close array fell upon them, and fought in a manner worthy of being recorded. They were the first of the Greeks, so far as I know, who introduced the custom of charging the enemy at a run, and they were likewise the first who dared to look upon the Median garb, and to face men clad in that fashion. Until this time the very name of the Medes had been a terror to the Greeks to hear.

The two armies fought together on the plain of Marathon for a length of time; and in the mid battle, where the Persians themselves and the Sacae had their place, the barbarians were victorious, and broke and pursued the Greeks into the inner country; but on the two wings the Athenians and the

defeated the enemy. Having so done, they suffered the routed barbarians to fly at their ease, and joining the two wings in one, fell upon those who had broken their own centre, and fought and conquered them. These likewise fled, and now the Athenians hung upon the runaways and cut them down, chasing them all the way to the shore, on reaching which they laid hold of the ships and called aloud for fire.It was in the struggle here that Callimachus the Polemarch, after greatly distinguishing himself, lost his life; Stesilaus too, the son of Thrasilaus, one of the generals, was slain; and Cynaegirus, the son of Euphorion, having seized on a vessel of the enemy's by the ornament at the stern, had his hand cut off by the blow of an axe, and so perished; as likewise did many other Athenians of note and name.

[...]

The Persians accordingly sailed round Sunium. But the Athenians with all possible speed marched away to the defense of their city, and succeeded in reaching Athens before the appearance of the barbarians: and as their camp at Marathon had been pitched in a precinct of Hercules, so now they encamped in another precinct of the same god at Cynosarges. The barbarian fleet arrived, and lay to off Phalerum, which was at that time the haven of Athens; but after resting awhile upon their oars, they departed and sailed away to Asia.

There fell in this battle of Marathon, on the side of the barbarians, about six thousand and four hundred men; on that of the Athenians, one hundred and ninety-two. Such was the number of the slain on the one side and the other.6

It seems prudent at this juncture to draw attention to the involvement of the god Pan in the Pheidippides legend. Pan was a critical figure to the Greeks, who regarded him as the god of hunting, shepherds and their flocks, the theater, and the wilder aspects of nature (including animalistic and uninhibited sexuality in many references). Indeed, Pan's places of worship were not typically temples, but rather natural caves or grottos.

Pan's entreaty to Pheidippides in this context is illuminating. Pan was said to have the power to frighten any present with his angry shout, a power likely attributed to him to explain the propensity of flocks to suddenly spook without obvious cause.7 Likewise, Pan is said to have aided the Greek gods in their conflict with the Titans by frightening them with his shout, or, in some sources, by causing a deafening roar by blowing into a shell.

Of course, this uncontrollable fear or terror combined with its baseless irrationality merged with the god's name forms the basic etymology of the word "panic."8

The Athenians clearly attributed at least part of their very one-sided victory during the Battle of Marathon to Pan, as evidenced by their dedicating a place of worship to him after the battle.

The "Cave of Pan" Endures on the North Slope of the Acropolis,

Even if the God's Potency is Long Gone- But Don't Be So Sure it Is.

The fact that Classical Greece (Greece's golden age) immediately followed the Battle of Marathon (though many historians peg the onset of Classical Greece somewhat earlier to 510 BC on the occasion of the overthrow of Hippias, the Athenian tyrant who, depending on how one counts such things, was the last of the Greek tyrants) is often cited in support of elevating the Battle of Marathon to the status of a sort of birthing event for everything from Western society at large to democracy, modern mathematics, philosophy, and the SPANX Slim Cognito® Shape-Suit (as seen in Women's Day magazine). Whatever your predisposition to such claims the throwing off of the Persian yoke was certainly a watershed event in the development of republics and democracies. After all, one cannot live freely with Persian appointed tyrants telling you what to do all the time.

However much (or little) one credits the role of the Battle of Marathon as a gateway to modern Western political structures, the strategic and tactical execution by the Greeks certainly serves as a model for coordination and communication among allies, discrete political divisions, or simply Greek city-states in a confederation or republic during times of emergency. The lines of communication and the mutual support arrangements of the sort in place with Athens and e.g., Sparta (though this ultimately proved unnecessary), and Plataeae were essential to the mutual defense of an association of city-states that would have been hard pressed to break free of Persian dominance in the absence of such pacts. Likewise, the sort of centralized control under a single leader that dominated the political structures of the era, while it might have made defense simpler, had proven highly incompatible with what most Western societies consider acceptable political structures today.

Certainly, the fact that the Persians failed to utilize their calvary well, and the resort by the Greeks to the raw battlefield tactics of the phalanx and the citizen-soldier model of the Hoplite contributed, but to finem respice's way of thinking these details fall under dimming lights when viewed against the brilliance of the enduring success of cooperative elements of the Greek poleis (city-state) model.

Recall that immediately before landing at Marathon the Persians had established three beachheads in Eretria at Tamynae, Choerea, and Aegilia:

But the Eretrians were not minded to sally forth and offer battle; their only care, after it had been resolved not to quit the city, was, if possible, to defend their walls. And now the fortress was assaulted in good earnest, and for six days there fell on both sides vast numbers, but on the seventh day Euphorbus, the son of Alcimachus, and Philagrus, the son of Cyneas, who were both citizens of good repute, betrayed the place to the Persians. These were no sooner entered within the walls than they plundered and burnt all the temples that there were in the town, in revenge for the burning of their own temples at Sardis; moreover, they did according to the orders of Darius, and carried away captive all the inhabitants.9

Almost certainly, the Persians expected similar behavior from the Athenians and expected them not to risk leaving their city undefended, particularly with the the threat posed by the possibility of a Persian fleet marauding about. A cloistered Athens would have permitted the Persians, who wanted Athens intact and their tyrant re-installed, to raze the coastal areas so critical to Athens. This threat was particularly daunting as the Persian fleet probably landed some time in early to mid September, harvest time for olives, grapes and so forth. Likely a seige would have followed, given greater effect owing to the blockade effect the Persian fleet would have had.

Instead, the Persians were stuck in their beachhead for something like 10 days before the Athenians, seeing perhaps that the Persian calvary was not the threat they had feared, engaged, sucked in the Persian center, and eventually double enveloped the static Persian beachhead and drove the surviving invaders into the sea.

Turning to the central concern of the instant prose finem respice draws the attention of the always erudite and informed finem respice reader to one Edwin Monroe Bacon. Bacon, a Rhode Islander by birth, at one time or another, rendered services to the Boston Globe, the Boston Post, the New York Times, and the Boston Daily Advertiser. In 1886, with George Edward Ellis, he published "Bacon's Dictionary of Boston," which, among other definitions of interest, included the following entry:

Athens of America, The. — An epithet applied to Boston for many

years, often in irony it must be confessed ; of which the origin seems to

be in one of the letters of William Tudor, describing the city in 1819, in which he says, "This town is perhaps the most perfect and certainly the best-regulated democracy that ever existed. There is something so imposing in the immortal fame of Athens, that the very name makes every thing modern shrink from comparison ; but since the days of that glorious city I know of none that has approached so near in some points, distant as it may still be from that illustrious model."10

Whatever the source, the nickname "The Athens of America" stuck and has been part of the self-identification mythology among Beantown elites for the better part of a century and a quarter- a bit of elitist signaling reinforced by one of the highest population densities of high-education affiliated residents in the country, not to mention the generally elevated trappings of self-opinion one finds prevalent in the Northeastern United States.

It should come as little surprise to the always highly analytical finem respice reader that the Boston Marathon regards itself as and is generally regarded by outsiders as the foremost and among the most selective of 26.2 mile events in the world. The city's self-identified association with Classical Greece only serves to cement this mythos to all that is inherently "Bostonian."

But, if finem respice were somehow to be persuaded of the validity of this noble association, how might the ancestors and ancient namesakes of the "Athens of America," (also known as the "City on a Hill," the "Hub of the Solar System," the "Cradle of Liberty," and the "City of Champions") regard the Massachusetts city-state today? It is difficult to imagine the answer to this question is anything other than:

"With manifest disgust."

It seems somewhat daunting that the "Cradle of Liberty" quite quickly resorted to dictating a state of affairs that even the linguistically cautious finem respice reader would be hard pressed not to compare to "martial law." Foremost, by instituting the increasingly popular "Shelter in Place" tactic.

Close the Gates! To the Walls!

"Shelter in Place" (along with used dry cleaning bags and duct tape) originally found popularity as a defensive tactic against nuclear, chemical, and biological attack. Civilians were advised to avoid going outdoors and to bastion their homes against the incursion of wafting fumes of death from various sources. Other than during the "North Hollywood Shootout" in 1997, most early instances of the tactic were related to natural or man-made disasters (gas leaks, refinery fires, chemical leaks, etc.). It is not at all clear that this use of "Shelter in Place" by police in the North Hollywood case was novel, but certainly in the ex post study of the North Hollywood shootout various authorities recognized that the power to compel pesky by-standers to draw their blinds and huddle under their desks while police operations were conducted was an awfully convenient arrow to have in the quiver.

Apparently harkened by the resounding "success"11 of off-the-cuff "Shelter in Place" tactics used by students in the library during the Columbine incident, many school safety plans began adopting a "lock-down" or "Shelter in Place" mandate in response to crisis incidents.

So prevalent has this tactic become that, just prior to the 2013 Boston Marathon, one could not go a single month without hearing about some institution or another (most commonly a school or university) that had gone on "lock-down" (with all the shades of a penal institution that evokes) in response to some scare or another (generally involving toasted pastries).

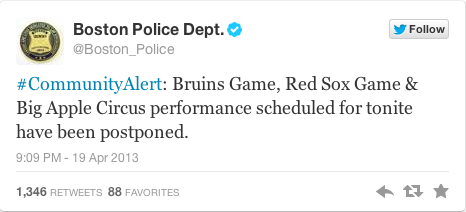

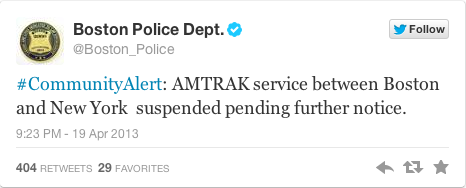

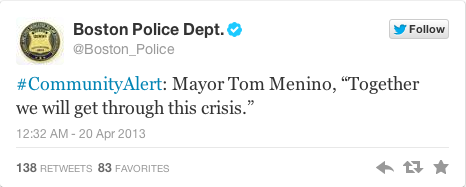

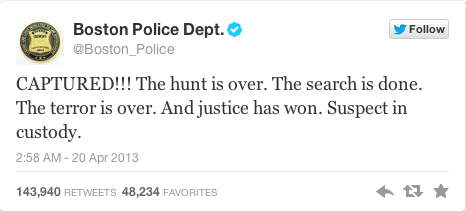

It was in this context that, in the five days after April 15th, the "Cradle of Liberty" would vacillate from sane, to manic, and back to sane again before finally lurching into the darkest depths of corrosive municipal insanity. We have social media to thank for the contemporaneous record of the "Athens of America"'s schizophrenic break and (partial recovery).

As the city geared up for the Marathon and was already feeling the effects of the influx of spectators, tourists, and those in town by virtue of their attachment to Marathon runners, the concerns of the Boston Police department in the day before the event seem almost quaint in retrospect (all times in UTC +02:00):

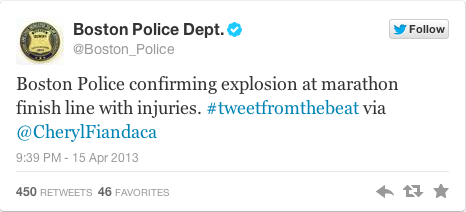

Not long after the bombs went off the Boston Police were confirming the explosion and the count was quickly 23 injured, 2 dead:

Not an hour later the Boston Police apparently were starting to worry about crowd control:

But fear not, everything is in hand:

Still, an augmented police presence should be expected:

Things continued in this vein for some time. Some limited street closures were announced. Eventually the news that the FBI was taking over the investigation was related. But the Boston Police couldn't help but ask for the public's help:

And eventually, some semblance of normalcy, at least such as could be expected, began to creep back into life:

In fact, the Boston Police Department was almost apologetic at the disruption:

But... perhaps a hint of things to come:

Still, everything is in hand. Keep calm and carry on:

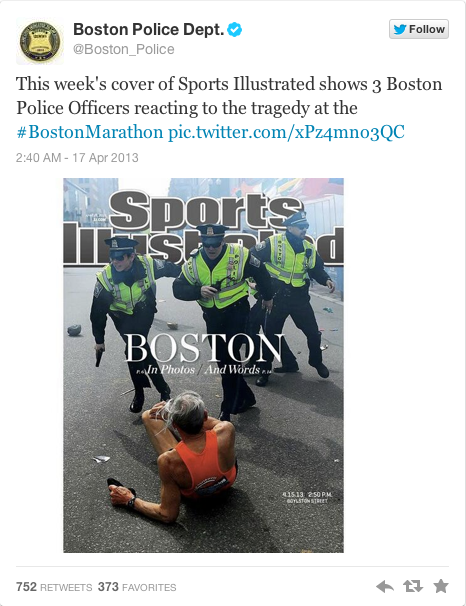

A time to revel in the outstanding response and importance of first responders, culturally:

It is Perhaps Worth Noting That This Athlete Got Up and Finished.

Things still looked mostly normal, if your standard therefore involves the Boston Police Twitter feed, on April 18th.

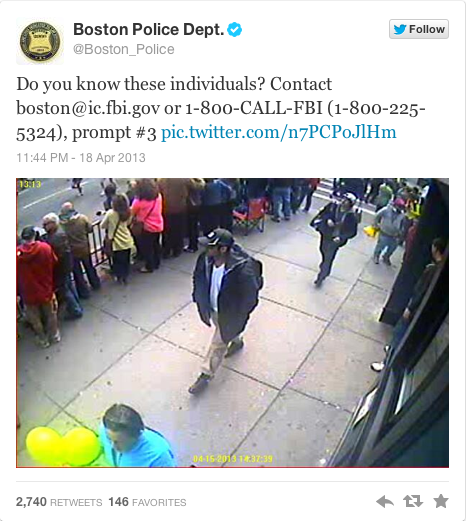

The Boston Police again solicited public help, and then posted the now famous video stills released by the FBI:

By April 18th the Boston Police must have been rather significantly tasked with preparing for the arrival of President Obama on his urgent mission to be photographed while comforting survivors and their families.

Phew! Got That Sorted.

Then... in the early morning hours... things escalated quickly:

This particular incident bears some notice and, upon some reflection, it proves quite illuminating.

Several sources point out that around 10:30-10:45 p.m. on Thursday April 18th, 2013 an MIT police officer is discovered shot in his patrol car. The officer is later pronounced dead on arrival at a nearby hospital.

Apparently, just after this event, the alleged Marathon Bombers carjack a Mercedes SUV somewhere in Cambridge, Massachusetts. According to the indictment against Dzhokhar Tsarnaev filed in the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts, one of the alleged Marathon Bombers indicates that:

The victim stated that while he was sitting in his car on a road in Cambridge, a man approached and tapped on his passenger side window. When the victim rolled down the window, the man reached in, opened the door, and entered the victim's vehicle. The man pointed a firearm at the victim and stated, "Did you hear about the Boston explosion?" and "I did that."12

The carjackers demand money from the driver and then attempt to take money out of his ATM account before either dropping him off or allowing him to escape about half an hour later (there's some discussion at the moment that suggests the victim was let go because he is not American). Here is the key point:

The carjacking victim escapes or is released and proceeds to report the carjacking to the authorities.

Armed with a description of the stolen vehicle, and the critical information that the carjacking victim's cellphone was still in the SUV, police triangulate the location of the phone and eventually spot the SUV about 4 miles away in Watertown. The timeline gets muddy at this stage, but it appears that after a brief chase during which the occupants of the SUV throw explosive devices at police, the occupants dismount and proceed to engage in an protracted shootout with six officers in which they also throw explosive devices at police.

The Tsarnaev Brothers Shelter in Place Behind the Mercedes SUV As Active Shooters

A number of residents filmed the incident and cameraphone video taken of the shootout at around 1:30 a.m. is dramatic. The neighborhood is peppered with stray rounds, some witnesses reporting that they stopped filming or watching after rounds zipped through the walls or windows of their abodes.

In the aftermath dozens of cars had their windows shattered or tires flattened by bullet holes.

Sources differ on what happened next, but it seems apparent that the elder of the two alleged Marathon Bomber siblings broke cover and charged police and either ran his firearm dry or had a weapon malfunction. He was then tackled to the ground by an officer while trying to clear the malfunction or reload and just before the younger sibling, now back in the SUV, seems to have driven directly at police, who scattered, and then over the older sibling, probably killing him, before escaping in the SUV.

The SUV was later found abandoned a short distance away. This meant that by around 2:00 a.m one Dzhokhar Tsarnaev was apparently on the loose in the "Cradle of Liberty." The aforementioned "Cradle of Liberty" then promptly proceeded to melt into a foul puddle of incontinent authoritarian insanity.

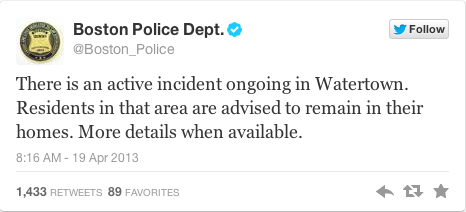

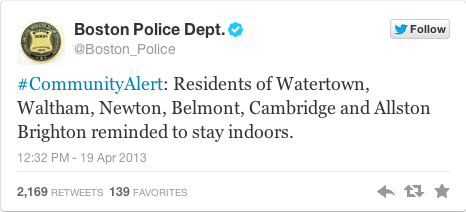

By 2:30 - 3:00 a.m. The Boston Police Department was certainly "asking" residents in Watertown to remain indoors. But, while some of the media would report these requests faithfully, not everyone did. Many "Shelter in Place" or "lock down" messages were reported as a "Shelter in Place order," a "lock-down order" or with language like "...residents are directed to stay in their homes." And the orders didn't stop there.

Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick issued a statement calling for residents to "Shelter in Place." Boston Mayor Thomas Menino got in on the action too at 8:10 a.m. on April 19th by using a statement that:

The City of Boston is urging City-wide shelter in place. As this investigation unfolds we are advising all residents, citywide, to shelter in place. Please understand we have an armed and dangerous person(s) still at large and police actively pursuing every lead in this active emergency event. Please be patient and use common sense until this person(s) are apprehended. We will continue to update the public with more information as it becomes available. All MBTA service remains suspended at this time.

By noon on April 19th the Associated Press was quipping:

Boston's police commissioner says all of Boston must stay in their homes as the search for the surviving suspect in the marathon bombings continues.

But the Associated Press wasn't alone in.. shall we say... augmenting the nature of the request into an order. Shelter in place "orders" or "requests" (depending on who sourced the instructions) were pushed out via broadcast SMS, reverse 911 robo-calls, press release, social media, etc. etc. etc.

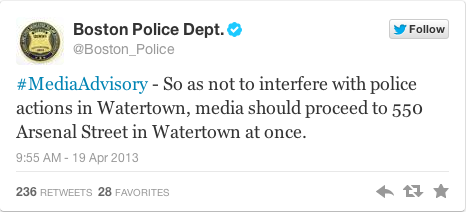

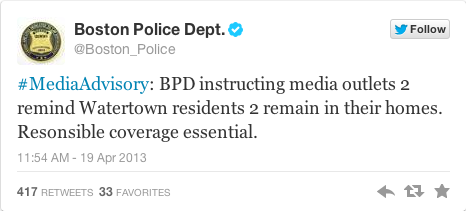

Of course, there was always a danger that the media wouldn't be cooperative.

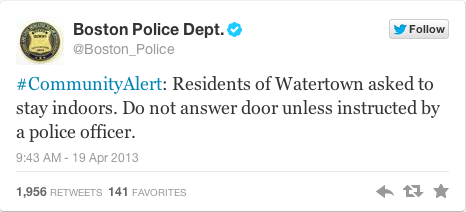

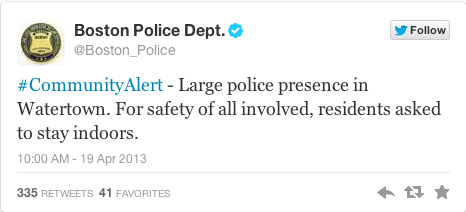

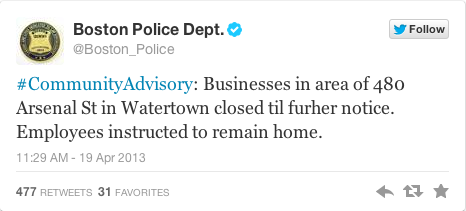

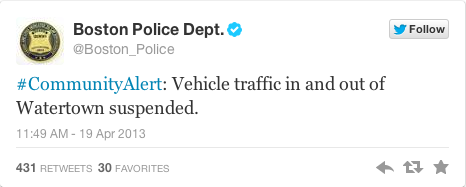

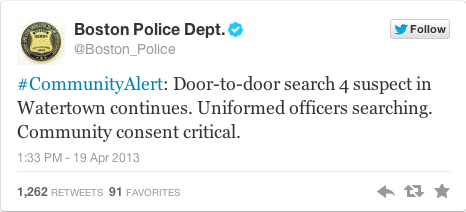

As the sun began to threaten to rise and the missing Tsarnaev hadn't yet been found the "lock down zone" expanded. By now the Boston Police Department didn't seem to be asking anymore:

Authorities also apparently worried that some might not take their frantic efforts in the spirt in which they were intended.

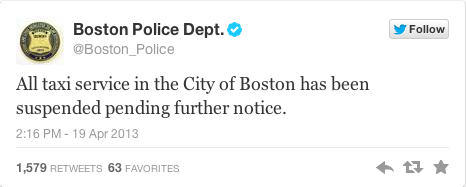

After a brief scare that the suspect had taken a taxi that possibility was abruptly dealt with.

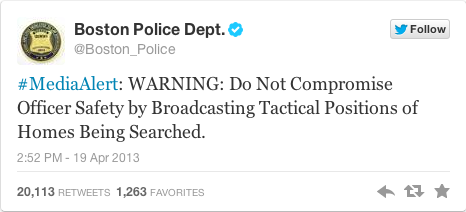

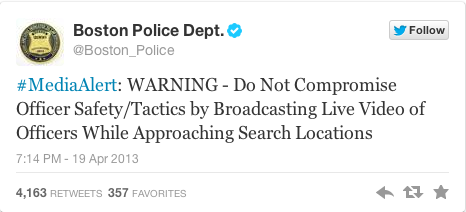

A number of residents, and others, glued to the developing drama took pains to Tweet every tidbit about the chase, including police radio traffic, and eyewitness reports. To say the authorities were unhappy is probably an understatement.

By afternoon, in their eternal benevolence, the authorities elected to spare those people who had gone to work the horror of having to listen to their co-workers speculate all day.

But there was to be no escape from the "Cradle of Liberty." Not even a figurative one.

Fortunately for the captive audience in the Cradle of Liberty, the authorities had some words of encouragement. Specifically:

"Together," eh? Evidently, "together" means "Sit there! Let it bleed! I'm going to go clean out the bank vault."

As it turns out, however, the captive audience in "The Cradle of Liberty" were a compliant bunch. As assault-weapon bearing bands of body-armored, black or camo-clad hulks fanned out through the neighborhoods door-to-dooring, skittish residents were systematically ordered out of or pulled out of their homes (some at gunpoint with hands raised). Some were frisked, or just interviewed and made to wait outside of their homes until authorities gave the all-clear signal.

Just when it seemed to be abating, the tension level would be jacked up again when some officer thought he perhaps maybe saw something that might well have been a sign that perhaps there might be someone in that residence. Dozens of uniforms and guns would descend on the spot, a megaphone would be produced, and brusk commands would be issued to the neighborhood in general and the house specifically.

At one point residents claimed a helicopter started orbiting and blaring orders from loudspeakers in a foreign language (probably Russian). One might well have expected to hear a stark cry of "Wolverines!" echo from behind the cover of a nearby garden just before an RPG streaked up in the sky to down the aircraft in a fiery hulk. (Don't worry Mrs. Winthorpe, you can file a claim for the RPG backblast damage to your prized roses after all this is over).

Viewers All Over the Country Watched the Tense Drama Presented by This Scene,

as Police Surrounded and Negotiated With an Empty House for Nearly an Hour.

This Empty House Refused to Negotiate with (or Even Respond to)

Bull-Horn Wielding Authorities for Over 45 Minutes, Even After the Arrival of the First Armored Division

The Media Was Eventually Forced to Stop Filming the Incident.

Meanwhile, the "Athens of America" was reduced to a ghost town.

Right around 5:00 - 5:30 p.m., after several hours of laying siege to the area around the abandoned SUV, searching door-to-door, and convincing dozens of empty homes to surrender without injuries or fatalities, the authorities held a press conference and admitted that they actually had no idea whatsoever where Dzhokhar Tsarnaev was and reluctantly announce they are lifting the "Shelter-in-Place" designation.

David Henneberry probably doesn't see this press conference, but he does hear that the "Shelter-in-Place" order has been lifted. Henneberry and his wife take the dog outside for a romp, and Henneberry fires up a much needed smoke. He then notices that the tarp covering his boat is flapping in the wind. On closer inspection he finds one of the tie-downs cut. Peeking inside he sees blood and.... he immediately calls 911.

Having recently distinguished themselves in action in the social media campaign and drawing on their recent experience in subduing inanimate objects, the authorities surround the boat, direct it to surrender, blind it with light from a helicopter, repeatedly flash-bang it, shoot at it, and generally carry on for the better part of an hour and a half. At around 8:45 p.m. Dzhokhar Tsarnaev (who may or may not have expended his last round of ammunition trying unsuccessfully to kill himself) surrenders to the FBI.

When Dzhokhar Tsarnaev is taken into custody he is less than a three quarters of a mile from where he abandoned the Mercedes SUV.

Terror is over! Justice has won! Thousands of revelers pour into the streets. Random meter maids are kissed on the street. Jubilant co-eds give their dorm room numbers to any man (and many women) in uniform.

It is definitely Miller Samuel Adams Boston Lager time. Well, one thing first:

Days of sage and responsible crisis management, teamwork, community outreach, overtime funding, sacrifice, and patriotism have paid off.

Except... not really.

In fact, not at all.

What has become the dominant narrative of the Boston Bombers investigation, pursuit, and capture is little more than a rank lie. It is a lie that conceals not just missteps, but what would, on reflection, be difficult to label as anything other than an overwrought, excessive, authoritarian police action that is primarily notable today for having demonstrated the absolutely peerless incompetence of the authorities in question.

Let us, just for a moment, take a step or two back.

The net result of the unprecedented city-wide lock-down was to bring to a grinding halt one of the largest and most economically significant cities in the United States. If the United States Department of Commerce is to be believed, the GDP of Boston is on the order of $300-$315 billion. In this respect it seems reasonable to assign a daily GDP to the city (and its surrounding areas) of something like $1 billion. It seems hard to escape the conclusion that, given the reaction of the authorities, for what probably didn't exceed a couple of thousand dollars, a community college drop-out and a failing sophomore at University of Massachusetts were permitted to cause more than a billion dollars in economic damage to the United States at large (and some substantial fraction of that to the "Cradle of Liberty.")

Given this sort of analysis one is caused to ask: "How many more such 'victories over terror' can the United States afford to win?"

But, expensive as they are, aren't these victories worth the cost? Well, perhaps. But unless you have some means to show that the costs are directly related to the victory it starts to become hard to justify them as necessary to the end goal. And in this case? To what extent were the decisive and leadership-imbued police actions in this case the proximate cause of this "victory over terror"? It takes almost no analysis at all to arrive at the conclusion: "Almost not at all." Consider:

All of the major ex ante efforts of the authorities were useless in this case. For instance:

- Despite repeated bomb sweeps before the event including the finish line area someone managed to deposit two powerful explosive devices right at the finish line.

- The diversion of traffic, security cordons, random sweeps with explosive sniffing dogs, and every other pre-race security provision were effectively useless.

- Despite having not a small bit of intelligence on the alleged bombers, and at least some warning from a foreign country that appears to have been Russia, no agency was engaged in anything proactive enough to deter or prevent the alleged bombers from completing their mission.

- The United States Immigration and Naturalization Service should simply be scrapped and rebuilt from the ground up.

All of the major contemporaneous security provisions were equally useless:

- Even a high degree of contemporaneous police presence at the Marathon (and particularly at the finish line) was effectively useless in preventing or deterring the bombers from planting and detonating their devices. First responders... aren't. Over and over again the key to effective response is almost always civilians at the scene, not police, firefighters, paramedics, or EMTs. Even in the case of a "public service rich" environment like the Boston Marathon's finish line the majority of assistance came first from civilians.

- At least in this context the "see something, say something" campaign and decades of "suspicious package" security education was apparently a waste of effort. Actually, it seems to have been a total waste of time overall. Really, if an ownerless backpack stuffed with a pressure cooker in the crowd at the Boston Marathon finish line isn't enough to sound alarm bells, nothing is.

With the except of medical and triage response after the bombings, ex post efforts were worse than useless. They contributed nothing to the search for and capture of the alleged bombers. Moreover, they were, in fact, devastatingly damaging.

- Effectively every key success leading up to the death of Tamerlan Tsarnaev and the capture of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev was the result of actions by private persons and entities, not the authorities. To wit:

-- The photographs and video that permitted the FBI to post images of the primary suspects (and eventually identify them) so quickly were taken by a private security camera installed outside a merchant's location near the finish line.

-- Once the photos and video were released it was private citizens that contacted authorities to identify the suspects by name.

-- It was details provided by the victim of the car-jacking, and the fact that the victim indicated that his cellphone was still in the carjacked SUV that allowed police to locate the stolen SUV so quickly, and thus led the police to the SUV in Watertown, which, in turn, led to the two suspects.

-- Despite this lead and having the element of surprise, police closed in without backup and the suspects spooked. In the absence of either Tamerlan's poor ammunition management skills or a weapon malfunction both may well escaped before a cordon was established and one officer almost lost his life on the scene.

-- Once he had escaped Dzhokhar barely made it a mile before slipping into David Henneberry's boat, wounded. Apparently, he manages to evade the attentions of police for hours here, despite being in the midst of the "lock-down" and "door to door search" area. Good work team!

-- Only after the "Shelter in Place" non-order order is lifted does civilian David Henneberry see something out of place that police officers, who lacked the degree of personal affinity (dare we even say... "love"?) for his boat that Henneberry clearly possesses may well have missed.

Aside from being entirely unprecedented, such large scale lock-downs and door-to-door search campaigns are not particularly effective unless one is trying to round up undesirables en masse for future disposition. (Your papers please!)

Given the volume of frantic, indiscriminate fire laid down by the six officers confronting the Tsarnaevs in Watertown (by some estimates 300-400 rounds were fired) the greatest danger to civilians at that point appears to have been from the police.

Good Thing He Wasn't Sitting In It.

Bullet Holes in Wall and Desk Chair in a Watertown Resident's Home.

Even assuming arguendo that the authoritarian actions of the authorities in this case were effective, their utilization prompts the ever curious finem respice reader to ask a few pointed questions. To wit:

Q. Were residents inside the "lock-down" area permitted to refuse entry to police conducting "door-to-door" searches?

Q. What were the consequences to residents who chose to ignore the "lock-down" "suggestion"?

Q. On the basis of what authority did the authorities suspend taxi service (presumably a private enterprise) in and around Boston?

Q. On the basis of what authority did the authorities order "Businesses in area of 480 Arsenal St in Watertown" to close?

Q. To what extent can "exigent circumstances" exceptions to the Fourth Amendment be extended city-wide, or across multiple cities and municipalities, on a level of granularity that permits authorities to literally enter any home in the city they please at any time?

Q. To what extent were these decisions made by the FBI, or federal authorities rather than local authorities?

Q. Which (if any) are verbs that indicate a police "order"?: "Police are instructing..." "Police are reminding residents to..." "WARNING: Do Not..."

It seems hard to escape the conclusion that many of these questions might never be answered. Local authorities in Boston have now had a taste of the expediency of extraordinary police powers which obviously run up to and include the power to paralyze an entire city to hunt down one man. It seems difficult to conclude that they will easily relinquish them.

It also seems difficult to conclude that sheep-like Boston residents will even notice. Despite the demonstrably astronomical odds of being nearby, much less wounded or killed by, either of the Tsarnaev brothers after the Marathon Bombs went off, Bostonians seemed almost eager to submit to the hysteria and hype purveyed by their masters and place their entire life on hold on the thinest of rationales.

From this perspective finem respice can't help but regard with wry amusement the assertion by various members of the media and law enforcement that social media somehow managed to spread dangerous misinformation during the crisis- as if Fratty McGreenline could do more damage after 12 hours of trying than a single tweet from the verified Twitter account of the Boston Police Department did by urging residents to "Shelter in Place" from dawn until dusk.

And here our journey comes full circle.

[Athena] was the goddess of metis, which means cunning and craftiness.... The word that we use today to mean the same thing, is really technology.... Instead of calling Athena the goddess of war, wisdom and macrame, then, we should say war and technology. And here again we have the problem of an overlap with the jurisdiction of Ares, who’s supposed to be the god of war. And let’s just say that Ares is a complete asshole. His personal aides are Fear and Terror and sometimes Strife. He is constantly at odds with Athena even though — maybe because — they are nominally the god and goddess of the same thing — war. Heracles, who is one of Athena’s human proteges, physically wounds Ares on two occasions, and even strips him of his weapons at one point! You see, the fascinating thing about Ares is that he’s completely incompetent....13

It would seem to finem respice that the "Athens of America" has abandoned Athena, let lapse the Athenian alliance with Pan so essential to the victory at Marathon, and instead finds itself in the thrall of Pan's angry shout. "Panicked," as it were.

In retrospect, far from perpetuating associations with Athens, it seems far more appropriate now to label Boston the "Eretria of America," besieged, sheltered in place, and, should this continue, soon to find itself enslaved by the modern equivalent of the Persian king Darius.

- 1. It should be noted that the pejorative meaning of "tyrant" is a relatively modern adoption, Plato apparently having driven the connotations of lawless rule present in contemporary use. Originally this Greek term was merely a descriptive title for an authoritarian ruler.

- 2. Merson, Luc-Olivier "Le Soldat de Marathon" (1869).

- 3. Jean-Pierre Cortot, "Le Soldat de Marathon Annonçant La Victoire," The Louvre, Département des sculptures, Richelieu (1822-1834).

- 4. Herodotus, "The History," Herodotus, Book I (c. 440 BC) (translated by George Rawlinson).

- 5. Herodotus, "The History," Herodotus, Book VI (c. 440 BC) (translated by George Rawlinson).

- 6. Herodotus, "The History," Herodotus, Book VI (c. 440 BC) (translated by George Rawlinson).

- 7. Graves, Robert, "The Greek Myths," Viking (2011).

- 8. panic, a. and n.2 (pænk) Forms: 7– panic; also 7 -ique, -ik, 7–8 -ick, pannick, -ic. [a. F. panique adj. (15th c. in Littré) = It. panico (Florio); ad. Gr. adj. of or for Pan, groundless (fear), whence neut. n. panic terror, a panic. ‘Sounds heard by night on mountains and in vallies were attributed to Pan, and hence he was reputed to be the cause of any sudden and groundless fear’ (Liddell and Scott). Stories more or less elaborated, accounting for the origin of the expression, are found in Plutarch's Lives (Langhorne's tr. (1879) II. 701/2), Polyænus' Stratagems (written c. 160 a.d.; cf. Potter Greece iii. ix.), etc.] A. adj. (Now often viewed as attrib. use of B.) 1. a. In panic fear, panic terror, etc.: Such as was attributed to the action of the god Pan: = B. 2. 1603 Holland Plutarch's Mor. 425 Sudden foolish frights, without any certeine cause, which they call Panique Terrores. Ibid. 1293 All sudden tumults and troubles of the multitude and common people, be called Panique affrights. 1647 Ward Simp. Cobler 11, I hope my feares are but panick. 1665 Sir T. Herbert Trav. (1677) 241 That great Army?were put into that pannick fear that they were shamefully put to flight. 1700 Dryden Fables, Cock & Fox 731 Ran cow and calf and family of hogs, In panique horror of pursuing dogs. 1770 Langhorne Plutarch (1879) II. 701/2 A panic fear ran through the camp. 1850 Merivale Rom. Emp. (1865) II. xiv. 134 A sound of panic dread to the populations of Italy. b. Of the nature of or resulting from a panic; exhibiting unreasoning, groundless, or excessive fear. 1741 in Johnson's Debates Parl. (1787) I. 386 The tumults of ambition in one place, and a panic stillness in another. 1824 Galt Rothelan II. iii. vii. 70 He cried, with a shrill and panic voice, for Shebak. †2. Of noise, etc.: Such as was attributed to Pan. a?1661 B. Holyday Juvenal 120 Which they thought might be prevented by making a loud and panick noise with brasen vessels. †3. Universal, general. Obs. nonce-use. a. 1661 Fuller Worthies xxiv. (1662) 77 Seeing sometimes a Pannick silence herein. 4. (cap.) Of or pertaining to the god Pan: as, Bacchic and Panic figures. 1890 in Cent. Dict. The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. (1989).

- 9. Herodotus, "The History," Herodotus, Book VI (c. 440 BC) (translated by George Rawlinson).

- 10. Bacon, Edwin Monroe, "Bacon's Dictionary of Boston," Houghton, Mifflin and Company (1886) p. 40.

- 11. 66% of deaths and nearly 60% of injuries inflicted during the Columbine massacre were suffered by students who "Sheltered in Place" under desks and behind shelves in the Library.

- 12. United States v. Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, Criminal Complaint (April 21, 2013). Thanks Popehat!

- 13. Stephenson, Neal, "Cryptonomicon," Avon (November 5, 2002) (by way of Instapundit).

Entry Rating: