Remembering the Rote Blandness of Chaos

It is difficult to find a devotee of the cinema who would not, on being asked to identify the most memorable performance by Dennis Lee Hopper, fail to quickly name Easy Rider or Blue Velvet. Reportedly, Hopper convinced Lynch to cast him in the latter, more sinister piece by calling him and declaring "You have to give me the role of Frank Booth because I am Frank Booth...." And though I will readily admit that Frank Booth still has the ability to haunt the darker (and even significantly taint some of the lighter) of my dreams in the solitary and quiet nights that inevitably follow a viewing of Blue Velvet (not least because it is so easy to imagine Hopper is merely playing himself in depicting Frank Booth) I am not sure Lynch's suburban nightmare would mark my answer. But then, if Lynch can be said to understand the cinematic navigation of the dark side, Hopper is (or "was," and, oh, how painful it is to make that correction) clearly the wise old man of the Sea of Darkness. Said Lynch of Hopper's effort in Blue Velvet:

Dennis had to have been through experiences on the dark side to have owned that character.1

Unspoken, but assumed, is the reader's familiarity with the chaos that is Dennis Hopper, a small but necessary piece of understanding that makes Lynch's assertion so obviously true that it simply requires no elaboration to the learned.

But, to my mind, Hopper's real essence comes out of the mostly (and sadly) undiscovered documentary "Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse," filmed (sometimes clandestinely) by Eleanor Coppola over the long course of Apocalypse Now's principal photography in Manila. I suspect only this sort of raw, unadulterated exposition could ever really demonstrate the degree to which Hopper hardly needed to act and still perfectly capture those manic and nightmarish roles he was adroitly cast for.

Coppola: I have Dennis Hopper playing a spaced out photojournalist with twelve cameras who is here because he is going to get the truth. You know, and it's all, phew, man. And he's a wonderful apparition.

[…]

Coppola: It's nice because this is the moment when Chief dies, that he looks up and sees this harlequin figure waving all the people away. He sees, like, essentially Dennis Hopper. Know what I mean?

[…]

Hopper: I was not in the greatest of shape, you know, as far as, like, my career was concerned. [It was] delightful to hear that I was going to do anything… anywhere.

When an alarmingly overweight, Marlon Brando, who commanded upwards of three and a half million dollars (in 1976 and against a total budget estimated at thirteen million or so) for a month of shooting, significant additional fees for any overage and who hadn't even bothered to read Conrad's "Heart of Darkness," on which Apocalypse Now's John Milius and Coppola penned screenplay was based, languished on location, Coppola, in no small measure due to desperation, simply stuck the three actors together in a dark, humid room and started to film.

Coppola: I mean, I had been afraid to even put Dennis Hopper and Marlon together, cause, Christ, I hadn't figured out what Marty [Sheen] is going to do with Marlon, what happens if I got crazy Dennis Hopper in there?

[...]

Coppola: So what I should do. Ah hah! What I should do is just shoot for the next three weeks irrationally. In other words, if I did an improvisation every day between Marlon Brando and Marty Sheen, would I at that time have more magical and in a way telling moments than if I just closed down for three weeks and write a structure that then they act, and the answer would be that I am much better off to do an improvisation every day.

The resulting raw footage is recipe composed of eight parts useless raving, one part distracted (and increasingly panicked) direction and one part… pure magic.

Said Coppola of the result:

And I'm feeling like an idiot, at having set in motion stuff that doesn't make any sense that doesn't match and yet I am doing it. And the reason I am doing it is out of desperation because I have no rational way to do it. What I have to admit is that I don't know what I am doing.

Of course, these sessions with Brando, Sheen and Hopper produced what is to my way of thinking one of the most deeply disturbing, claustrophobic and memorable groups of scenes in modern cinema. But then, it is often the mark of the most formidable creative minds that they consider their own work inadequate.

One wonders tangentially, could any production bond a young Dennis Hopper today?

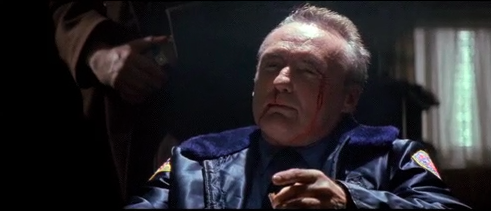

Later, of course, Hopper managed to harness his mania and energy into the crisp, professional craft one sees in his performances across from, e.g., Christopher Walken in the Tarantino scripted True Romance (1993).2

Dennis Hopper as Clifford Worley in True Romance.

-click to play- [71.9 MB .mov]

As I remember Hopper, who I had the great honor to be introduced to in Paris some years ago, my recollections will evoke the range of expression covered in this scene far more than the barely contained (and alarmingly captivating) flirtation with insanity that was Frank Booth or the unnamed "photojournalist" of Copolla's jungle nightmares.

"The thing about insanity..." Hopper began out of nowhere, or perhaps on some off camera cue to which he alone was privy, "...is that it is so approachable." Just a hint, a whisper of that familiar, manic laugh I had heard so many times in film but never in person escaped him- abbreviated, softer, but easily recognizable nonetheless. In a flash, just for an instant, I saw Frank Booth. A reminder that his sublime connection with the unsound, though schizophrenic, was not entirely forgotten. He continued, speaking to everyone, to no one and to me, somehow all at once, "It hides nothing, you know. That's so boring."

But then, who but Hopper could, eventually, find the raw power of chaos simply… dull?

Dennis Lee Hopper

1936 - 2010

- 1. Bary Egan, "Keeping Your Hair On," The Irish Independent. (November 4, 2007).

- 2. So many interesting details and tendrils thereof populate this scene. Look for a younger James Gandolfini in the background, a brief preview before his scene opposite Patricia Arquette, laced spectacularly with the most indelible violence and imbued with a performance ("Alabama, where's our coke and where's Clarence, and when's he coming back?") that almost certainly won him his signature role as Tony Soprano. The music, from Lakmé, also haunts "The Hunger," also directed by Tony Scott. And who can forget the chromed, prop Heckler and Koch P7 wielded by Walken that nearly brained Scott, leaving him dazed and bleeding on the floor when Hopper demanded the director demonstrate on himself how "safe" it was to fire the weapon against his forehead.

Entry Rating: